|

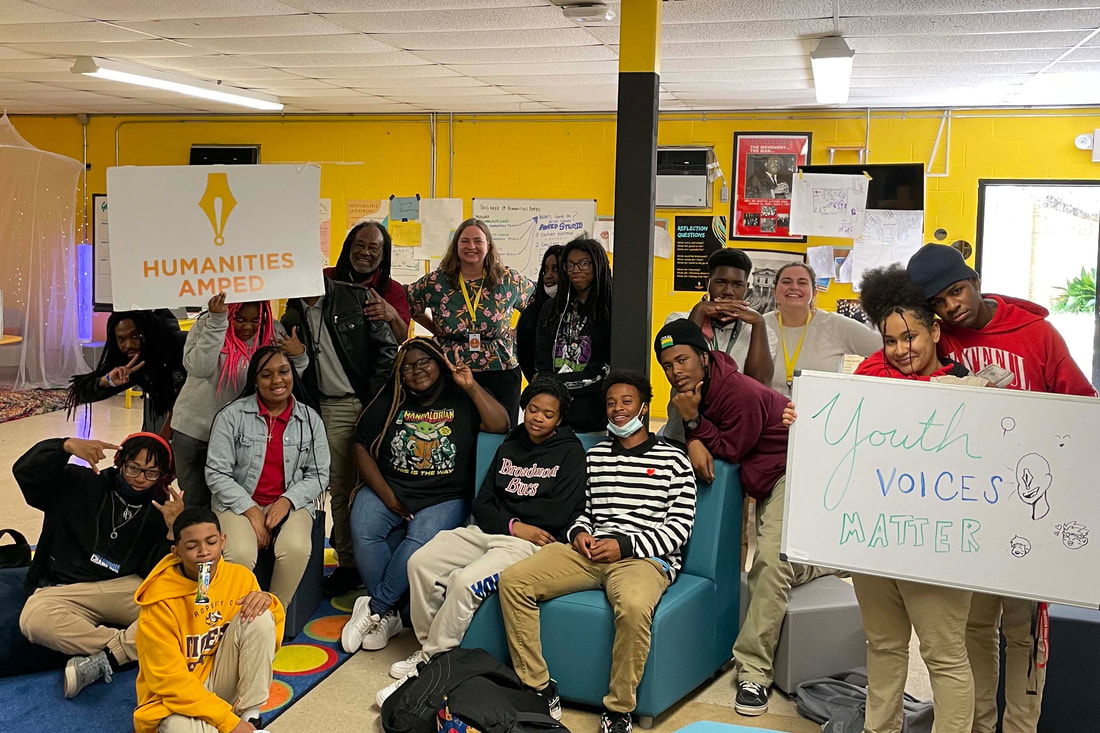

At Humanities Amped, our work to amplify healing justice, radical imagination, and beloved community in public schools and youth organizations is only possible because of your support. You, dear Amped family, are bringing transformative possibilities to life for students in the East Baton Rouge Parish Public School System. Because of your support, we are amplifying an ecosystem of hope at Broadmoor High School. As of this school year,

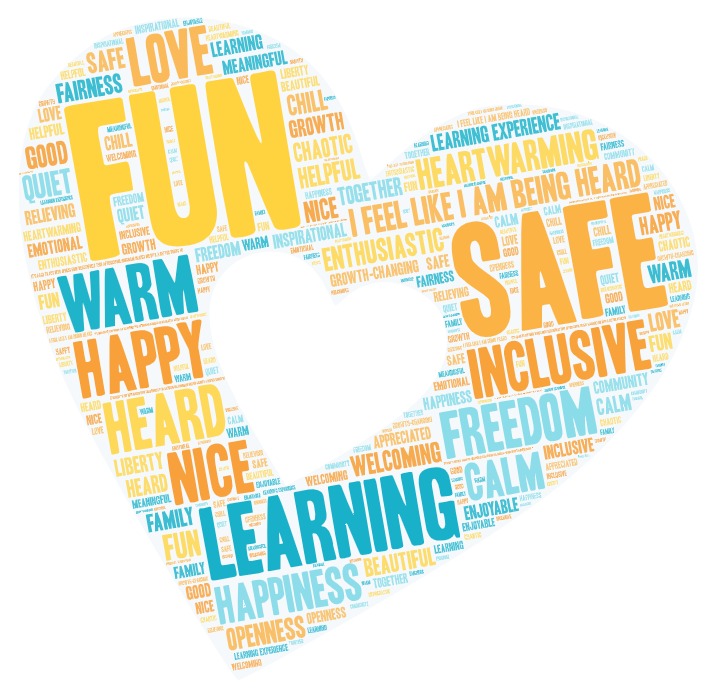

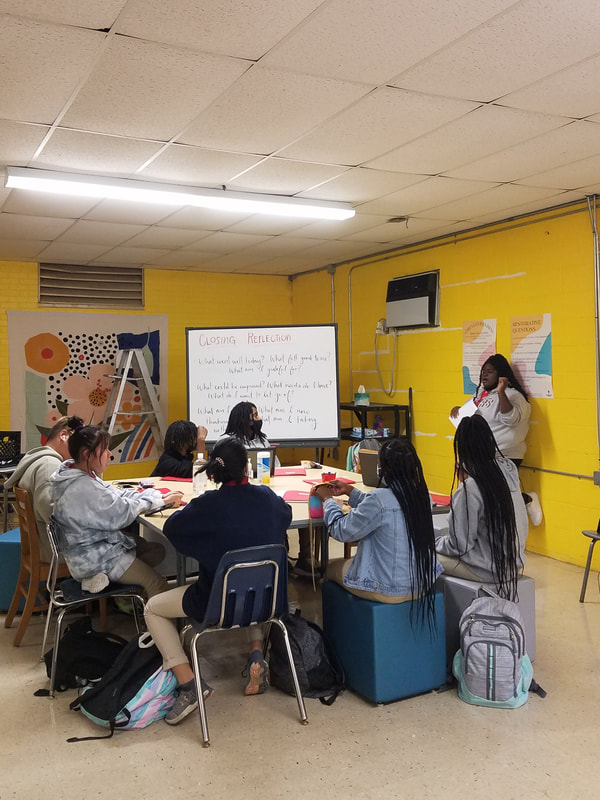

A recent survey of youth in Amped Studio Afterschool shows that 96% feel very supported by the adults in Humanities Amped, and 90% strongly agree that if they have a problem they can go to Humanities Amped for support. When asked what three words they would use to describe Humanities Amped, our students offered inclusive, welcoming, warm, fun, and safe, among other equally powerful descriptors. One student shared with us, “I’ve gotten a lot better at expressing what I feel and not being afraid to ask for help.” Another said that at Amped Studio, “It feels like I'm actually being heard.”

Amped family, thank you for pouring into the youth of Baton Rouge. We are proud to be in this work with you.

0 Comments

This week of the #AmplifyHope drive we're celebrating beloved community. Did you follow our beloved community think piece series last year? You can find the whole collection here! This year, we need your help to spread the word! If you believe in the mission of Amped, we hope you'll help us tell our story. Check out this video about how we center the value of beloved community, and send it on to someone you think should know about us!

We invite you to amplify hope with us by donating at the link below, and by helping us promote this video on social media! Every like, comment, and share helps us expand our reach, so let's #AmplifyHope together! The Amplify Hope Campaign, our yearly fundraising drive, begins today! Our work to empower public school communities and youth organizations to cultivate healing justice, radical imagination, and beloved community is only possible because of our family of supporters. This year, we need your help to spread the word! If you believe in the mission of Amped, we hope you'll help us tell our story. Check out this video about how we center the value of radical imagination, and send it on to someone you think should know about us! We invite you to amplify hope with us by donating at the link below, and by helping us promote this video on social media! Every like, comment, and share helps us expand our reach, so let's #AmplifyHope together!

Amped family, we are so pleased to formally introduce you to our two newest program managers: Mr. Zach Williams and Dr. Reva Hines. Both Zach and Reva add incredible value to our team, and we are proud to celebrate them with you!

What do you most enjoy about your role at Humanities Amped, and what are you looking forward to? My role at Humanities Amped allows me to work collaboratively with other educators who are passionate about youth development beyond just academics. I love working with young adults in these critical moments of their socialization, and Humanities Amped allows me to address the whole human that walks into our doors. Our young people are expressive, talented, and intelligent but do not always get to showcase all three aspects. I love that we provide a space for that and that they are developing a loving community with our guidance. Why does the mission of Humanities Amped matter to you? The Humanities Amped mission matters to me because the public school system does not always have the resources or capacity to foster the aspects of healing justice, radical imagination, or beloved community. The unfortunate reality is that many students do not feel as though they are truly part of the community they engage with on a daily basis, let alone having the power to heal what ails the community or that they have the power to create a new reality for that community. Since our focus is not individual academics and competition for opportunity, our students can become more well rounded as community leaders who have the capacity to claim their humanity and humanize others.

What do you most enjoy about your role at Humanities Amped, and what are you looking forward to? I enjoy being a part of Humanities Amped's learning community which offers a safe and brave space for our youth to be their authentic self all while accentuating their academic, personal, and social-emotional skills through healing and restorative practices. I am looking forward to cultivating and sustaining practices that build our youth to be the next generation of change leaders in our communities. Why does the mission of Humanities Amped matter to you? It is important for the youth to have a platform to grow. That's why Humanities Amped matters to me. It allows for just that to happen. You can catch Zach and Reva facilitating Transform Yourself Studio on Mondays and Wednesdays after school, conferencing with students who need support throughout the day, or offering guidance to students in Dreamkeepers as they navigate their options for after high school. Are you looking to support Amped financially? Head to our support page to donate today! We cannot do this work without you. Are you looking to get involved with Amped? Our call for volunteers is still open!

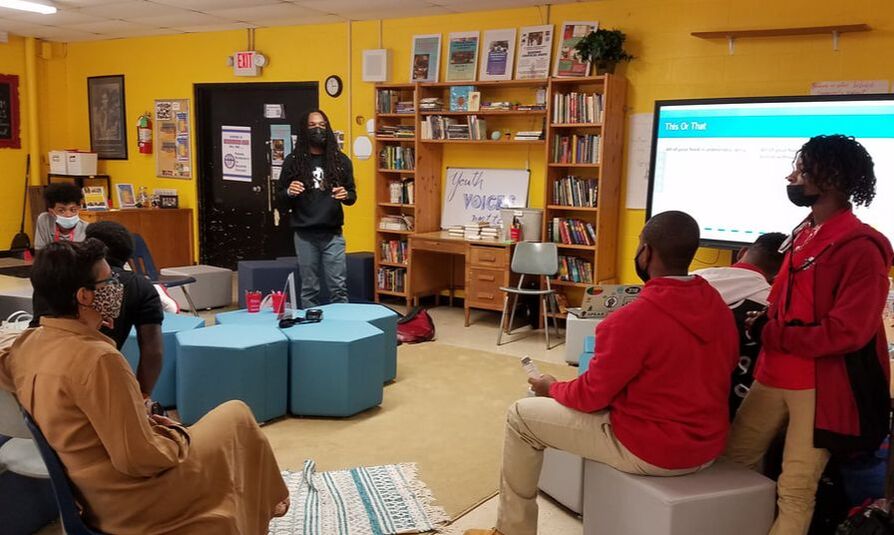

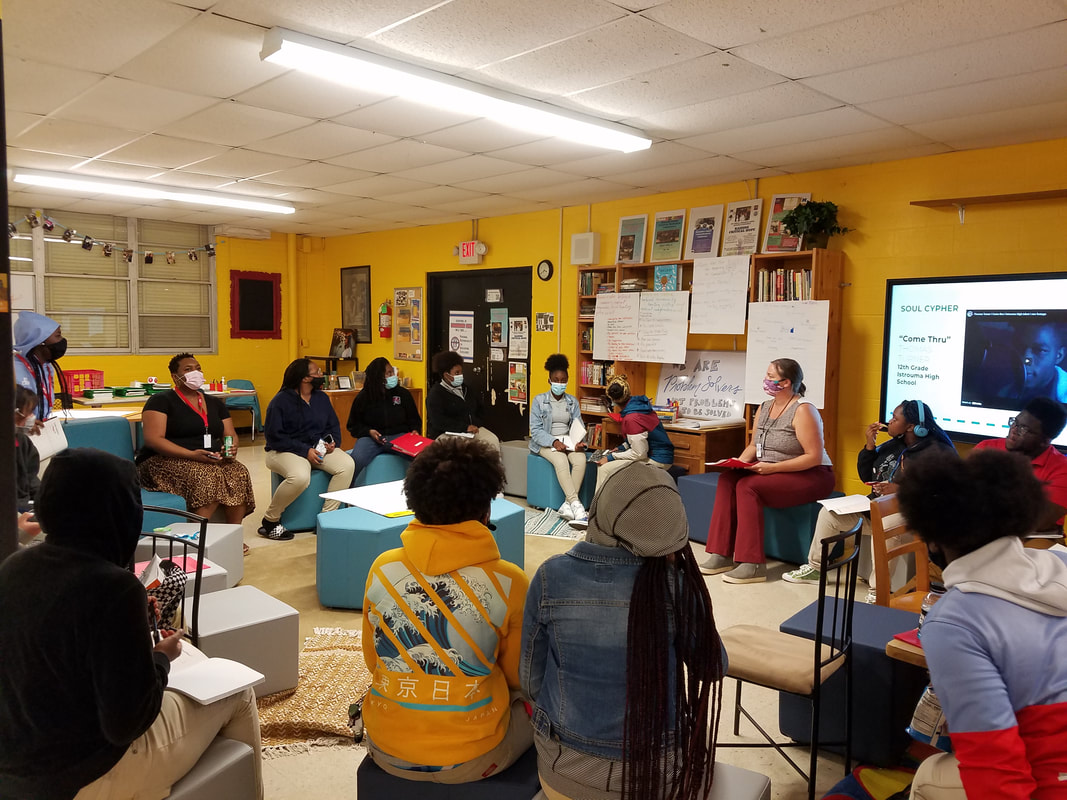

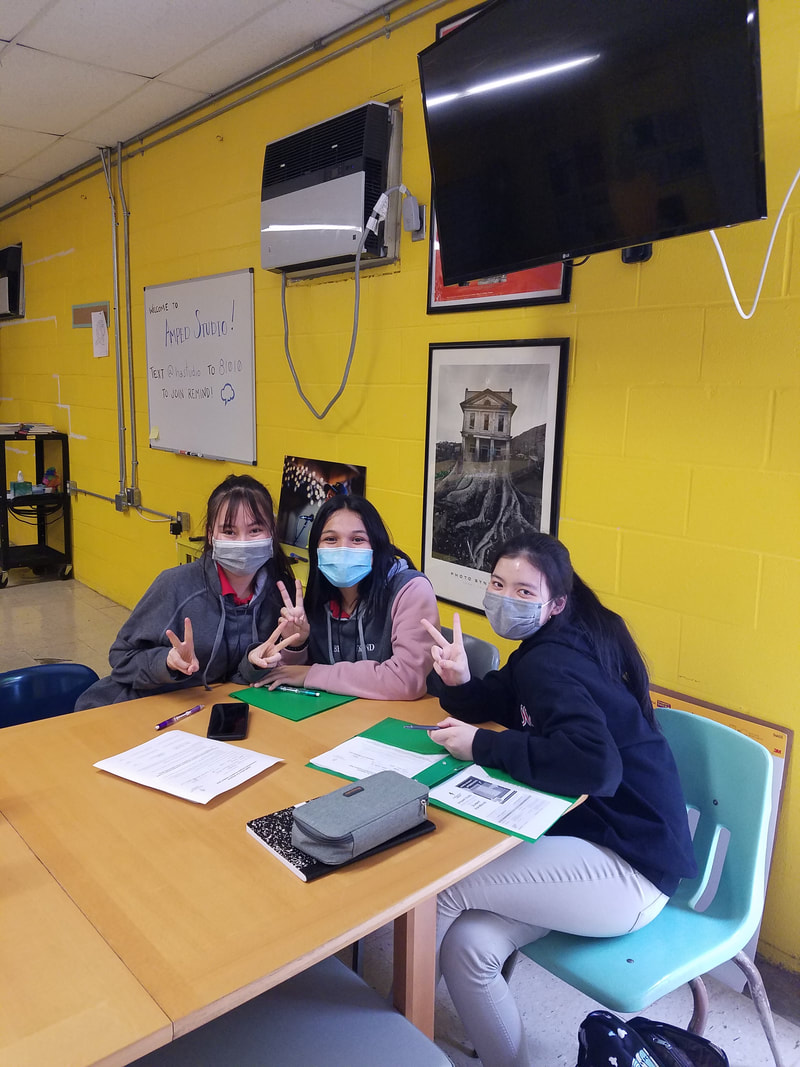

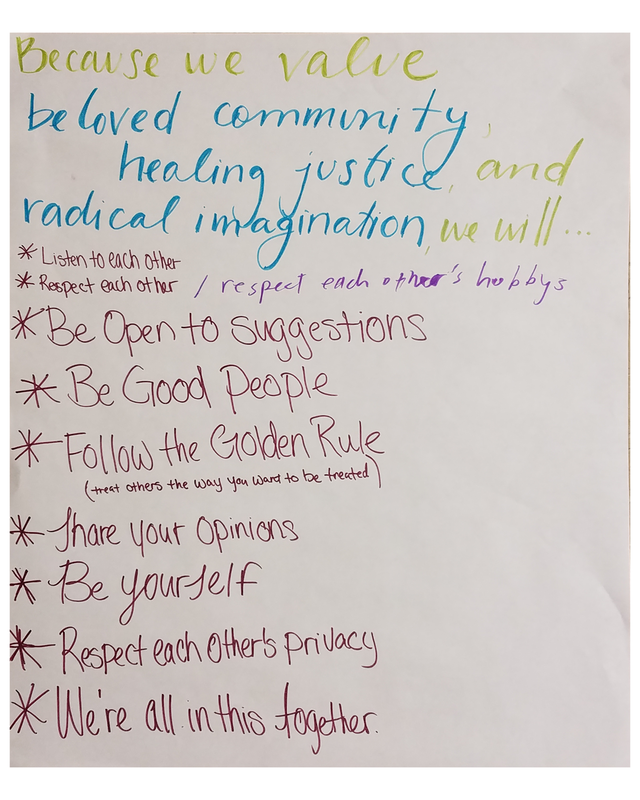

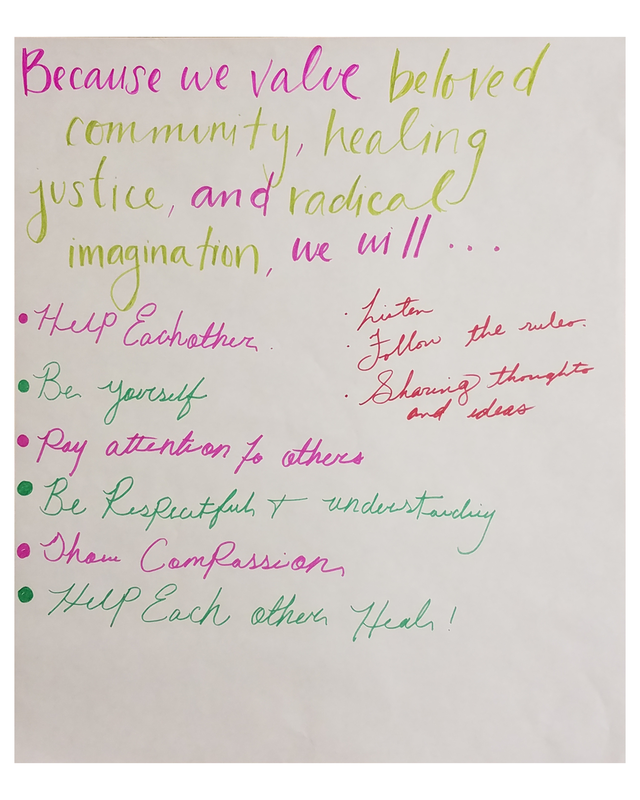

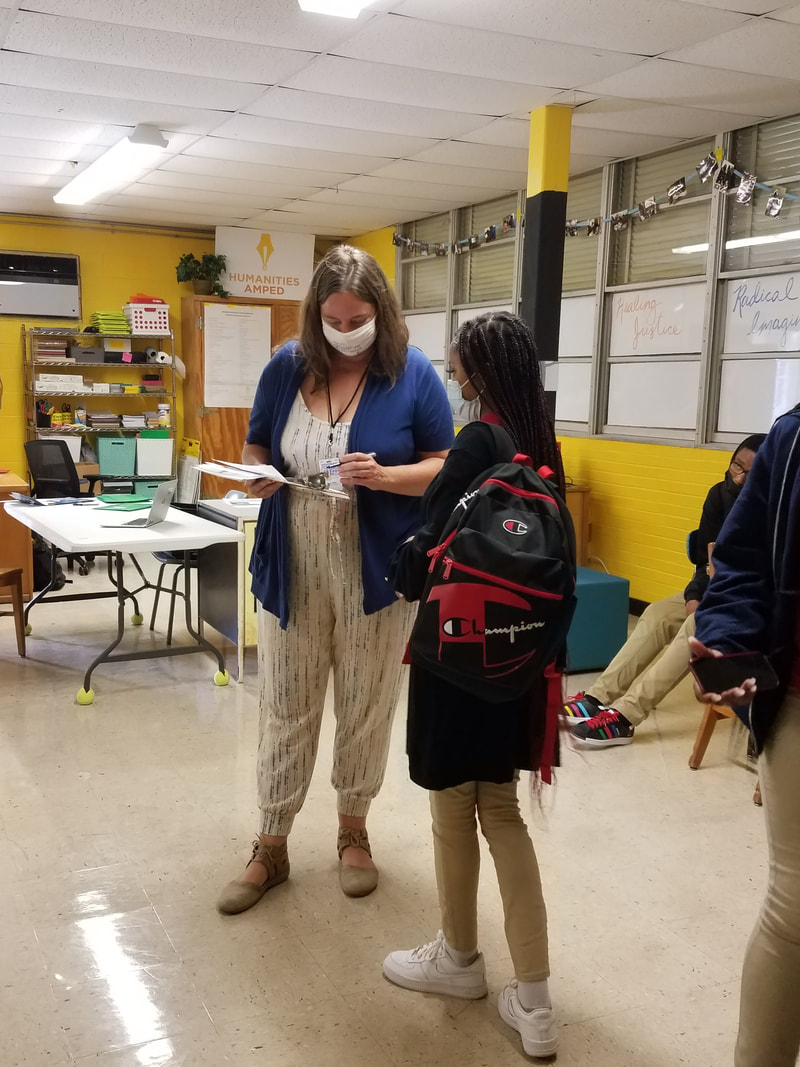

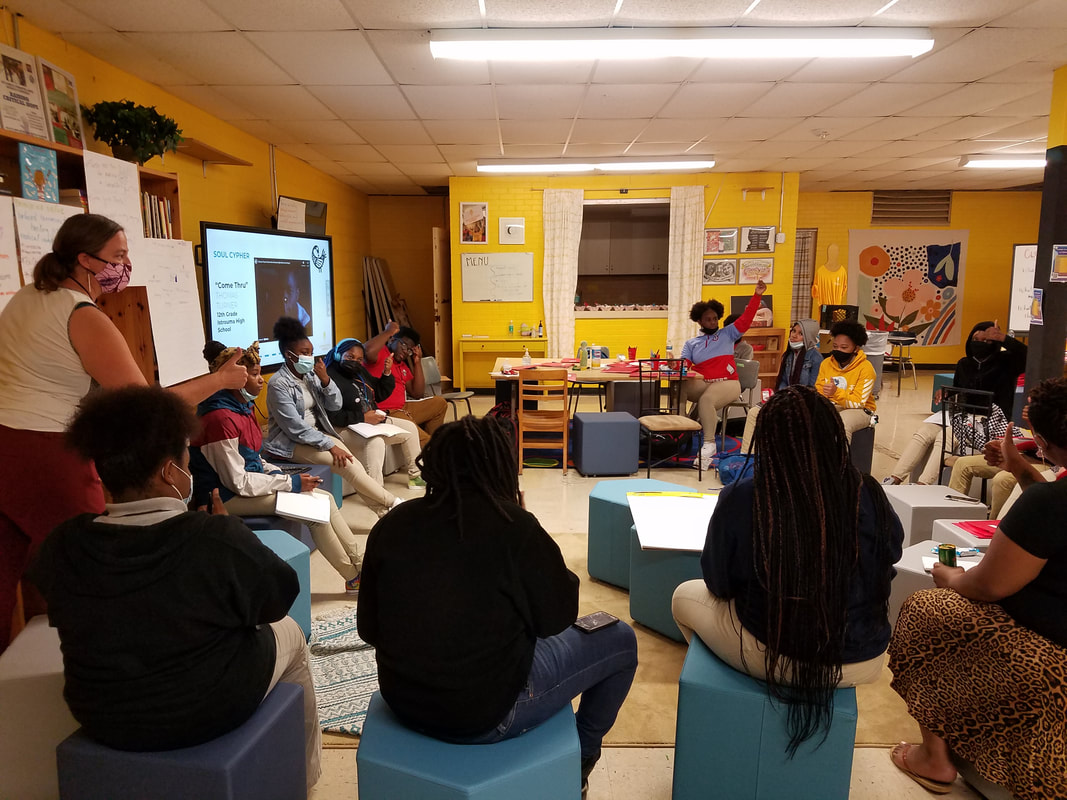

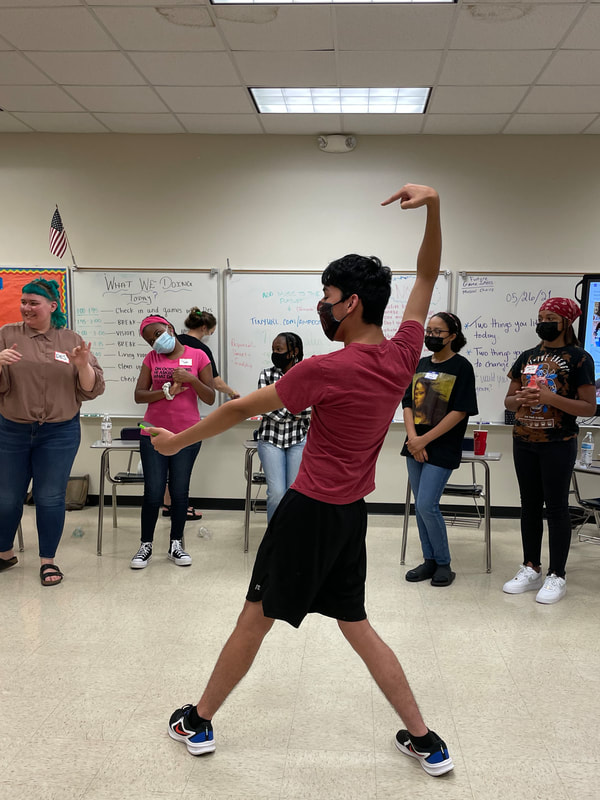

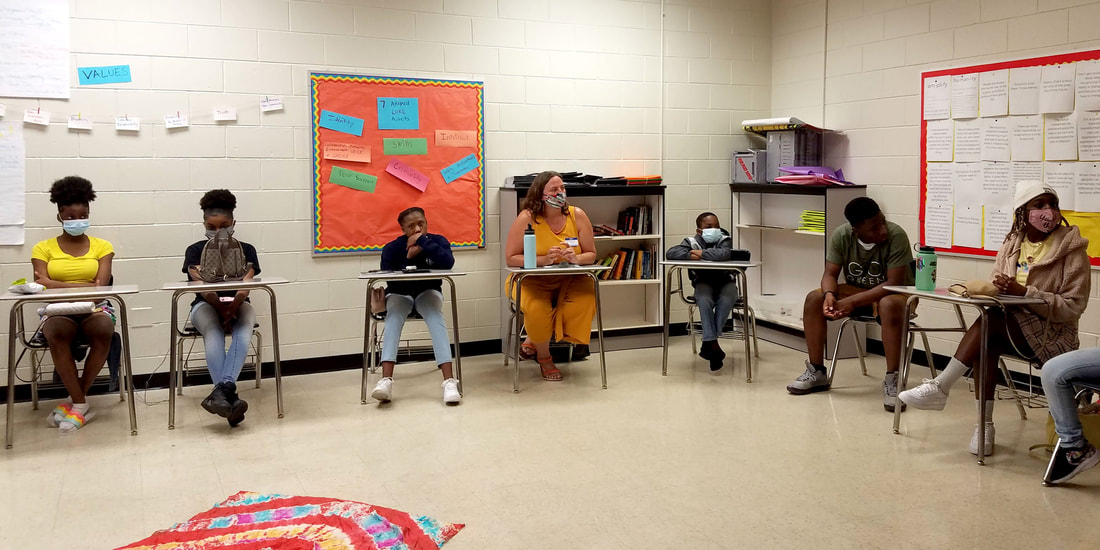

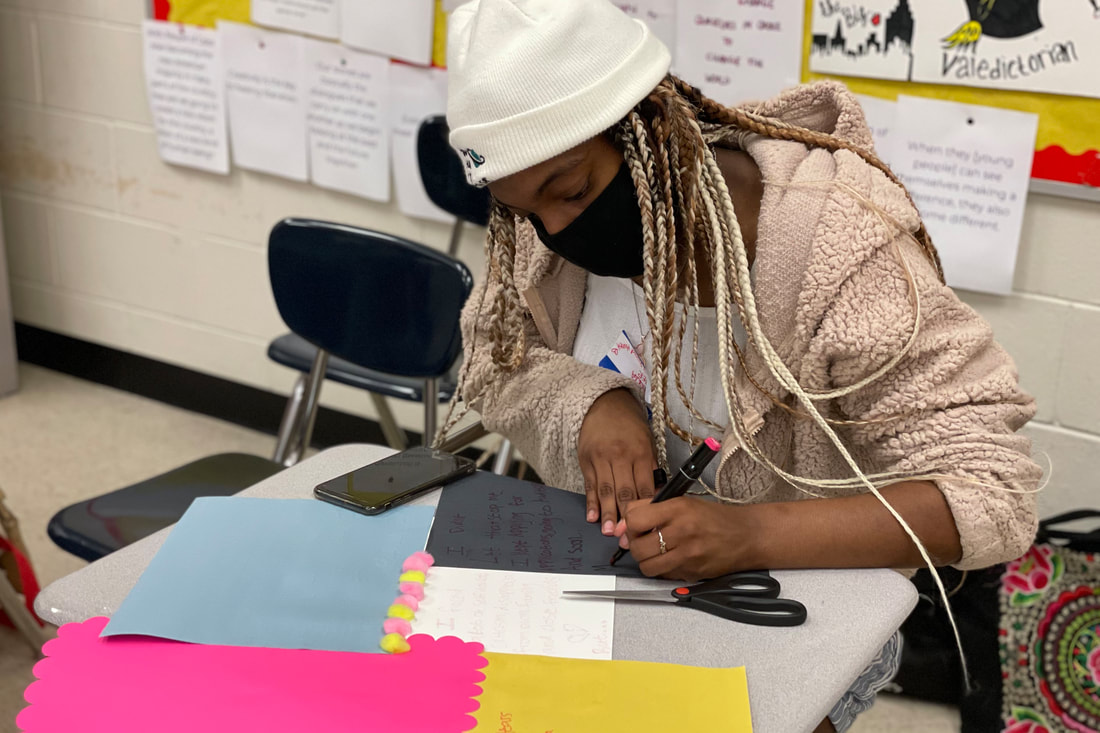

Amplifying ELA Classrooms is a project that will take place during the Spring 2022 semester at Broadmoor High School and specifically focuses on supporting the English Language Learners who make up 21% of the Broadmoor community. Volunteers will be matched with a Broadmoor teacher and work with them in their classroom throughout the semester on a weekly basis. You do not need special training to join this initiative, but you do need commitment, a heart for youth, and at least three hours a week that you can volunteer at a consistent time. Sign up by following the link below! If you have questions, please reach out to rhines@humanitiesamped.org. Amped Studio Afterschool at Broadmoor High School kicked off at the end of September with a lot of love and excitement in the air. On Mondays and Wednesdays students gather after school for Transform Yourself Studio, a supportive community that gives students space to set goals and provides them with the homework help, social emotional skills, and tutoring support they need to reach those goals. At Transform The World Studio, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, students are invited to apply their talents and gifts to be the change they want to see in the world. Enrollment filled up quickly, and after just a few weeks of programming we are already seeing the impact of careful attention to building beloved community together. Our first few weeks were focused on establishing a culture that is driven by young people: students created agreements that align to our core Amped values and reflect how they want to treat each other, and be treated, in Amped Studio. A student "culture keeper" reviews those agreements at the start of every session. This commitment to honoring the norms we set together is one way that students are claiming Amped Studio as a space for themselves to practice beloved community, healing justice, and radical imagination not as lofty ideals, but as everyday ways of being together that change the world. Students in Transform Yourself Studio engaged in an exercise to set visions for the lives they most want to live in the future. They then created goals for how they want to use their time in tutoring studios on Mondays and Wednesdays to help them achieve their vision. After the first time breaking into tutoring studios, one student shared in our closing reflection that she now feels "hungry" for the science test that had previously felt like a chore. By aligning student-driven goals with a supportive environment to reach those goals, we hope to amplify hope across campus. One day at a time, Broadmoor High students are experiencing real paths to achieving their dreams. One afternoon in Transform the World Studio we asked, "What does your own creative studio space look like?" Students wrote poems and drew pictures, made collages, and opened up to a deeper conversation about what it feels like to be in a space where you can truly express yourself. After a group conversation about pronouns and gender identity grew from the group's dialogue, one youth asked Dr. West, "Where were you all last year? I've really needed this." We are so grateful to be grounded this year at Broadmoor High School where we're able to build this beloved core of youth leaders who will contribute—and are already contributing—so much to our world. Amped Studio is amplifying our own hope for the future of our work as we imagine possibilities for the rest of this school year and beyond. Big dreams and visions are welcome at Amped Studio, and we can’t wait to see them bloom! If you would like to make a contribution to Humanities Amped, please follow the donate button below. This work is not possible without you!

Amped family, we are thrilled to introduce to you the newest member of the Amped team, Dr. Leslie T. Grover! Dr. Grover brings to her work as Program Director two decades of experience in youth programming, indigenous research, social justice organizing, curriculum development, and community engagement. She is an avid social justice scholar and has published extensively in the fields of race equity, health equity, and community engagement. In 2016 she was appointed as an Interdisciplinary Research Leader with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as well as community outreach specialist for U.S.-Cuban relations. She is also a creative writer, and her first novel debuts in Fall 2022.

Dr. Grover's enthusiasm for the work is contagious, and we are so grateful for the expertise and compassion she carries. As Program Director Dr. Grover will plan and implement initiatives like Community Care to provide social and emotional learning and restorative supports, as well as dynamic leadership opportunities, to the students we serve. The start of each new school year is always a busy time for us, and 2021 has certainly been no exception. The East Baton Rouge Public School System’s new social and emotional learning initiative fits so well with Amped’s commitments to healing centered and culturally responsive learning, that they’ve asked us to create a social and emotional learning community lab school. Humanities Amped is excited to share with you that we are now in residence at Broadmoor Senior High School! As you know, our work can only thrive in community, and this move to a single school site means that we will be able to work deeply with students, teachers, administrators, and families, as well as EBRPSS, to realize the vision of a community lab school for social and emotional learning. Over the last month we have engaged with faculty and staff to begin drafting a vision for what we’re calling Broadmoor’s radical imagination of what education can and should be, and we look forward to the start of Amped Studio Afterschool in which we invite students to to transform the world, through project-based action research, and to transform themselves, through tutoring and supports. We have also been hard at work making our space in the Broadmoor Galley warm and welcoming. We are enthusiastic about the district’s and Broadmoor’s commitment to social-emotional learning and look forward to building with our new Broadmoor family! If you would like to support the mission of Humanities Amped by giving, we invite you to follow the link below. Your contributions will help us to continue to transform our space on Broadmoor's campus and develop our programming. What's New at Humanities AmpedWe’re hiring for two positions: Program Manager (full-time) and Program Leader (part-time, Amped Alumni preferred). Send your cover letter and resume to hiring@humanitiesamped.com by September 17 to apply.

Starting in March of 2021, Humanities Amped has released a series of think pieces celebrating the first of our three core values: beloved community. As we head into the bustle and promise of this new school year, we are excited to share the last installment in the Beloved Community series with you.

TOGETHERNESS IS CHANGE WITHIN A BELOVED COMMUNITYTareil La'Kisha GeorgeWe sometimes forget the most important thing about being human is change. We have the ability to change whatever we want, but we seem to forget the importance of relationships, patience, and vision. One thing that I observe about us as humans is that we adapt. We learn adaptation from our environment. Adaptation isn’t a bad thing; for example, the poisonous Primrose has made a special adaptation so it could survive in desert-like areas. Humans are like the Primrose. We adapt to live, but why don’t we normalize changing the world, so we don't have to depend on adaptation to Survive?

In Amped, we often have our students create their own Norms, which give them the opportunity to set up their own rules to live by within the classroom. One Norm that students often request is ‘Active Listening’. Active listening is the biggest part of the listening and understanding skill. If you are actively listening, you are opening your mind to be more understanding of what’s going on in the space. As part of teaching, once you understand, the next moving part is to now focus on transforming what you have learned or relearned onto the next, but how and to who? This is where teaching and those three relationships start to develop. We have to see teaching as a way of better communication that recognizes students as unique individuals. We are taught that we should use what we have learned in the future, but learners may miss what is being taught based on how it is given. For example, you wouldn't teach a four year old the same way you teach a fourteen year old. You must have the balance between patience and understanding of their differences in order for them both to understand what is being taught. This also plays a role in relationship building. Without a relationship with those you are teaching, you would have a hard time being heard and understood. Being the listener of the youth, which can change the direction of better communication within the community, forms a relationship of understanding which can propel the sense of a Beloved community.

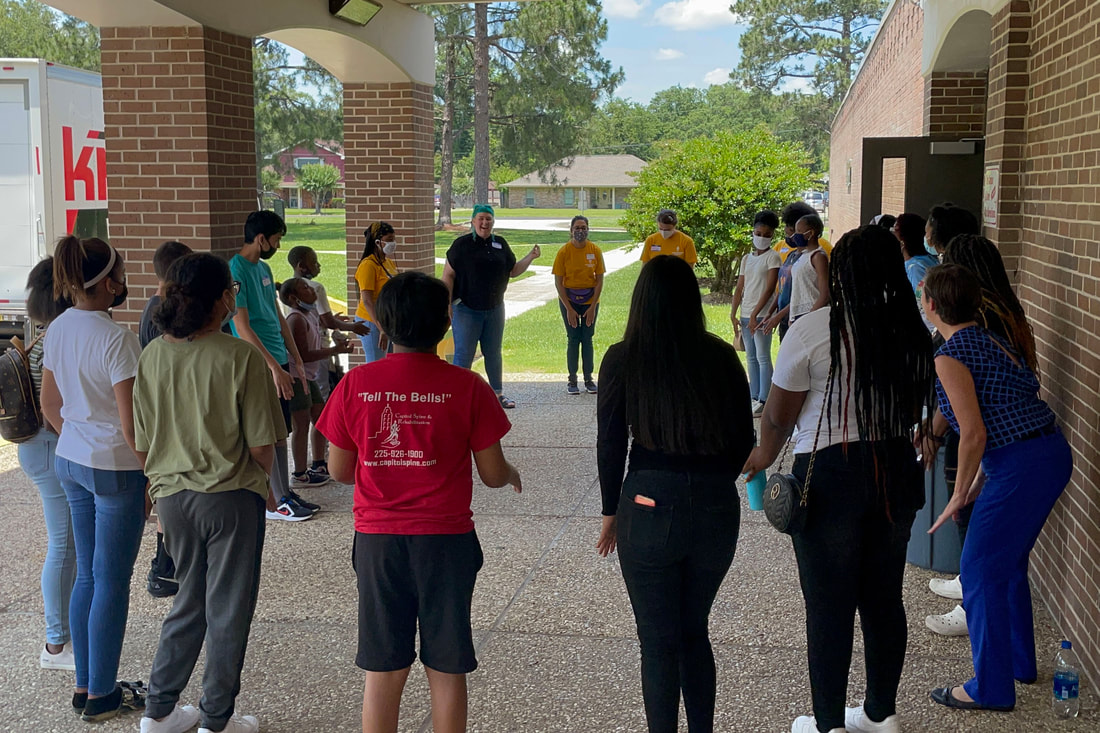

Amped Summer is in full swing! We started off the season with three weeks of summer programming that served a diverse group of youth from around the district. Our Amped Summer campers ranged in age from 13 - 19 and represented 11 schools! During week one students set the norms and values they wanted to uphold as a summer community. They made vision boards, got to know each other, and engaged in a variety of workshops hosted by Amped Instructional Specialist Destiny Cooper, ICARE Specialist Aubrey Jones, and peer-counselor Tonja Myles. Former therapist Wanda Kuo led an intergenerational dialogue on mental health as well as a virtual yoga session. During the second week, teachers and community members were invited to join students and summer staff as we watched the Grace Lee Boggs documentary American Revolutionary. Dr. Anna West facilitated a powerful workshop in which Amped youth and “elders” exchanged stories with one another. Later that week Dr. Leslie Grover and Dr. Reva Hines of Narrative4 led active listening sessions and theater exercises. They also gave students disposable cameras for an auto-photography project. In the third week, Amped board member Dr. Andrew Kuo set up his portable recording studio so students could record the poems, songs, podcasts, oral histories, and other projects they had been working on. Summer Amped concluded with a DreamKeepers College and Career Readiness Institute. Representatives from Southern University, EBR’s Office of Career and Technical Education, LSU, and BRCC led workshops and presented about their institutions to help students prepare for the futures they desire. To get a true sense of the Summer Amped experience, we invite you to read this “I Remember” poem, written by one of our campers during a virtual writing workshop. I Remember by Imani Morris, 8th gradeI remember the sweet smiles of everyone’s faces on the first day of camp I remember the sweet taste of star cut apples I remember us all being shocked at some of the things we saw in the American revolutionary documentary I remember the big group introductions I remember the snacks we managed to eat in 1 week I remember the deep conversations of our small groups I remember the acceptance of others stories I remember the crying laughing of my group for the theatre activity I remember using up 20 disposable camera shots in 1 day I remember sitting talking to sydni while we waited for our mothers I remember using up the whole break trying to figure out the board game clue I remember doing a recording for the first time I remember the messy clothing left behind from tie dye I remember the endless debate on whether it’s shein or she in I remember trying to come up with rhymes when we rapped And, I remember the people I met along the way -I.M With the close of Summer Amped, we are moving gratefully into a time of collective rest by taking a shared hiatus from June 19th - July 19th.

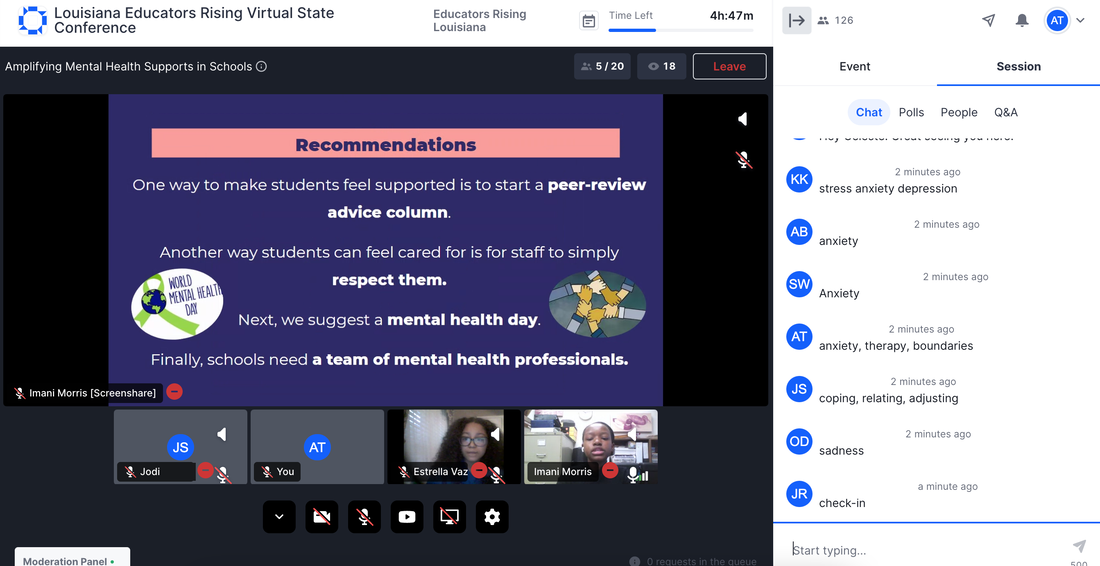

Our team at Humanities Amped is invested in long-term, sustainable, collective care, and we know that commitment begins right where we are, in our own lives. Showing up for ourselves means being intentional about slowing down and resting. It’s how we re-ground ourselves and build our capacity to show up for the long run. It’s never an easy choice to care for ourselves. There is always so much to do, and for those of us whose work is caring for our communities, we often feel like it is never enough. And yet we know that if we want to show up wholeheartedly, we must invest in our own restoration. We hope to come back to you filled with energy, insight, and imagination. You, dear ones, deserve nothing less than our best selves! See you in late July. :) Love, The Amped Team When Estrella, Sydni, and Imani witnessed their classmates and friends struggling with mental health and mental health services at school, they knew they wanted to create a pathway toward change and support. In order to reimagine in-school responses to students’ mental health needs, the trio of Amped Apprentice Leaders worked collaboratively with each other and their mentors to develop an action-research project: throughout the spring semester they facilitated dialogue, information sessions, and problem-solving circles driven by data they collected from their peers and community about mental health and Baton Rouge schools. Sydni, Imani, and Estrella were able to share their important findings with multiple community audiences. "In my experience, my school was worried about my grades and not my mental health. My school seems to care more about things like dress code than they do about mental health,” Sydni told me, as we prepared for the trio to lead an intergenerational community circle. The three middle school students walked me through their project: their motivations, their driving questions (“How to decrease the stigma around mental health in schools and school systems?”), and their own personal stakes relating to mental health awareness and services in schools. They had already facilitated their circle twice before engaging our Beloved Community circle participants, and they were ready to facilitate it a third time for our community. The seeds for this CPAR (critical participatory action research) project were planted in Amped Studio Afterschool, where we gave young folks in our community the space and opportunity to share and explore their own mental health struggles and triumphs. In Humanities Amped, we often find ourselves asking what comes first: civic engagement, community building, or storytelling? Imani, Estrella, and Sydni prove that they run alongside each other as three interconnected root systems that nurture us, carry us, and support us. Through this support and their friendship and commitment to their community, the trio created a dynamic, well researched, and heartfelt presentation. Even though our plans for this year did not include a student research conference as they have in the past, Imani, Sydni, and Estrella saw and acted on an opportunity to illuminate, articulate, and educate. They presented their research project three times: at Roots Camp, at the Educators Rising State Conference, and at the Humanities Amped and Baton Rouge Community College Beloved Community Check-In Circle. Through mentorship, support, and readily available platforms and pathways, Imani, Estrella, and Sydni were able to implement their vision for change as thought leaders in our community. Through scaffolding and framework support, they were able to offer us all a performance of possibility: with a whole community supporting and rooting for us, we can enact the change we need.

At Humanities Amped in 2021, we are celebrating the first of our three core values: beloved community. As we look toward the future and its challenges, this aspect of our organizational vision, to nurture a dynamic, beloved community of lifelong learners and civic leaders, has never felt more essential to our individual and collective well-being. Over the next few months, we will release a series of think pieces reflecting on the theme of beloved community and how it shows up in our work at Humanities Amped. Click here to learn more about the heart of beloved community, and read on to learn about one way it shows up in our work.

Beloved Community in a Virtual |

| To me, building a beloved community felt like it had to happen in person to be meaningful. But to my surprise, these last few months of Amped Studio virtual after school programming have demonstrated that a beloved community will form because people will want it to. On Mondays during DreamKeeper office hours, we form community when students have the opportunity to ask questions about topics they are most interested in, ranging from future careers, physical and mental health, and gendered double standards in sports. Since we serve five different schools, students from across campuses have had an opportunity to engage with one another in conversations that are relevant to them. While we have an Amped staff facilitator helping guide the overall dialogue, the students are the ones taking ownership of the conversation. In the virtual space of DreamKeepers I’ve often found myself feeling like I have the great fortune of tuning into a podcast run by extremely passionate middle and high schoolers. Amped staff Diana Aviles and Tareil George follow up on Wednesdays with tailored career and college readiness workshops, inviting alumni to engage with current students and give their perspective of life after high school. Through these visits the beloved community is expanded across generations of Amped students, renewing energy to both groups. | What would community building look like when we could not sit in a circle or toss a ball or snack together in the same space? |

But to my surprise, these last few months of Amped Studio virtual after school programming have demonstrated that a beloved community will form because people will want it to. | The camp counselor in me often wants to play games as a means of building community. And while the focus of Tuesday Tutoring implies an emphasis on academics, the virtual games we play on Tuesdays have largely become a motivating factor for students to get their homework done ahead of time. We have certified science, math, and English teachers available to help students with their homework, and students do take advantage of this opportunity to work one-on-one with a teacher. However, my favorite moments on Tutoring Tuesdays are when Ms. Burbank and Ms. Hammond join community volunteers and students in the game room to play trivia. Or when Mx. Araneda does a science experiment demonstrating the electrocution of pickles just for the joy of it. Teachers getting to have fun with their students is a radical form of beloved community, especially in this era of ultra pressurized, high-stakes testing that strips both students and teachers of the joy of learning. |

And finally on Thursdays, our students continue to go deeper into conversations about mental health and ways that students can offer peer support to one another. In December, a group of students designed and facilitated a mental health wellness workshop for youth at Big Buddy who have since requested to have other cross-collaborative virtual activities. And even though we did not have a critical participatory action research project planned for students this year, one organically emerged from our afterschool program: the constant conversations around mental health and the concern students have for one another’s well-being were fertile ground for three middle school students, Imani, Estrella, and Sydni to embark on a research project around the gaps in mental health services in school. They designed a survey with the help of teachers and have shared their findings at two local conferences - Roots Camp and Educators Rising.

| A virtual, intergenerational, cross-campus beloved community formed through Amped Studio despite the Zoom fatigue, a global pandemic, and many other barriers that unfortunately kept other students from being able to join in. This year we have watched our beloved community expand across the interwebs and reach students, teachers, staff, and volunteers in a meaningful way I had not thought possible. I’m very happy to have been proven wrong about my perceived limits of community. | Teachers getting to have fun with their students is a radical form of beloved community, especially in this era of ultra pressurized, high-stakes testing that strips both students and teachers of the joy of learning. |

In the spirit of amplifying youth voice, I believe the best way to close is to leave you with the words of 13 year old Sydni, an Amped Apprentice Leader who has found in Amped Studio space and support to thrive:

"I am so grateful for Humanities Amped giving me a space to just be. If I want to improve my grades, we have Tutoring Tuesdays, and if I want to start preparing for high school and college they provide me the resources to do so in our Dreamkeepers sessions. We have meaningful discussions in every class, but those discussions can really grow on our Thursday classes and I'm also able to express my thoughts in the form of writing on Wednesdays. I'm very appreciative of Humanities Amped for letting me grow.” •

"I am so grateful for Humanities Amped giving me a space to just be. If I want to improve my grades, we have Tutoring Tuesdays, and if I want to start preparing for high school and college they provide me the resources to do so in our Dreamkeepers sessions. We have meaningful discussions in every class, but those discussions can really grow on our Thursday classes and I'm also able to express my thoughts in the form of writing on Wednesdays. I'm very appreciative of Humanities Amped for letting me grow.” •

RSS Feed

RSS Feed