What is Youth Development?

Positive Youth Development is a field that emerged in the 1990’s as a way to speak back to damage-centered youth policy that focused primarily on prevention and harm-reduction. By replacing the question, “How do we prevent youth harm?” with the question, “What services, supports, and opportunities do youth need to develop in a positive way?” the emerging field of PYD overturned deficit-based assumptions about youth with an asset-based lens. In Positive Youth Development 101: A Curriculum for Youth Work Professionals, Jutta Dotterweich (2015) explains:

|

We define positive youth development as an approach or philosophy that guides communities in the way they organize services, supports, and opportunities so that all young people can develop to their full potential. There are several key, research‐based principles underlying this approach:

|

Over the past twenty years, these new foundations of positive youth development have been informed by insights from the emerging field of critical youth studies that urge PYD practitioners to pay closer attention to the broader political and social contexts that shape youth development. As Ginwright (2003) explains, “solid youth development programming addresses young people’s need for meaningful social engagement with the injustices and inequalities that circumscribe their lives while at the same time meeting their developmental needs” (p. 6). Kirshner and Ginwright (2012) argue that more attention should be paid to African American and Latinx youth and the political contexts of development shaping their lives, meaning the “ways that young people experience policies in their schools and communities and how they participate in solving problems as political actors” (p.1). This shift towards youth organizing does not dichotomize individual healing and the struggle to shift collective conditions; indeed, these are intimately linked goals. In a framework that he calls “radical healing” (2010, 2016), Ginwright calls for more investment in youth organizing as a means to facilitate positive youth development.

Why Youth Development?

While youth organizations who engage young people in out-of-school contexts often work from a youth development framework, this approach to working with youth is too often missing in K-12 educational settings. Nevertheless, educators who are committed to youth-centered classrooms that are culturally sustaining know that they cannot isolate learning from the human, social, and political contexts that shape their students’ lives, nor would they want to. A goal of Humanities Amped from the start has been to humanize education, which means engaging those larger contexts of students’ lives in our pedagogies. By doing so, we are sustaining life lines through networks of caring relationships, bringing forth spaces in which collective well-being and individual well-being are prioritized, tapping into community cultural wealth, and transforming schools into what they were always meant to be: spaces that prepare humans for full participation in global democratic citizenship.

Like the Detroit Future Schools (now People in Education), which formed in response to activist and philosopher Grace Lee Boggs’ call for a humanized education in which selves and structures are transformed, we learned quickly in the journey of Humanities Amped that “for our program to be effective in transforming classrooms, we had to transform not only students, but also the adults” (Saidi, et al., 2015, p. 8). We learned that teachers who desire to teach a humanized student must choose to engage in the process of becoming a humanized teacher: a teacher who learns openly and who presents and reflects their own learning and struggles with learning to their students. When teachers embrace, model, and reflect on their own learning with their students, classrooms shift from content-centered to learning-centered. In this type of environment, students are taught how to learn, not just what to learn, and through the teacher’s models of learning, students are inspired and develop a vision for their own personal growth. Humanized/humanizing teachers are aware that they must model interpersonal skills and personal growth in order to inspire students and create a trusting environment in which students are willing to take on the risks of growth and learning that an education requires. In other words, another compelling reason to engage youth development in our classrooms is that it promotes our own healthy adult development, giving “grown folks” the sense of hope and possibility that we also need so that we can do more than survive, but also thrive along with the young people whose lives are so deeply connected with our own. As our student Lauryn once put it, “Seeing young people trying to change things about the world inspires adults, because most adults believe that young people don’t care about their community, so seeing a young person make a change is a mindset change for adults.” Indeed, adults need this mindset change more than we are often willing to admit.

Like the Detroit Future Schools (now People in Education), which formed in response to activist and philosopher Grace Lee Boggs’ call for a humanized education in which selves and structures are transformed, we learned quickly in the journey of Humanities Amped that “for our program to be effective in transforming classrooms, we had to transform not only students, but also the adults” (Saidi, et al., 2015, p. 8). We learned that teachers who desire to teach a humanized student must choose to engage in the process of becoming a humanized teacher: a teacher who learns openly and who presents and reflects their own learning and struggles with learning to their students. When teachers embrace, model, and reflect on their own learning with their students, classrooms shift from content-centered to learning-centered. In this type of environment, students are taught how to learn, not just what to learn, and through the teacher’s models of learning, students are inspired and develop a vision for their own personal growth. Humanized/humanizing teachers are aware that they must model interpersonal skills and personal growth in order to inspire students and create a trusting environment in which students are willing to take on the risks of growth and learning that an education requires. In other words, another compelling reason to engage youth development in our classrooms is that it promotes our own healthy adult development, giving “grown folks” the sense of hope and possibility that we also need so that we can do more than survive, but also thrive along with the young people whose lives are so deeply connected with our own. As our student Lauryn once put it, “Seeing young people trying to change things about the world inspires adults, because most adults believe that young people don’t care about their community, so seeing a young person make a change is a mindset change for adults.” Indeed, adults need this mindset change more than we are often willing to admit.

Youth Development: Curricular Guideposts

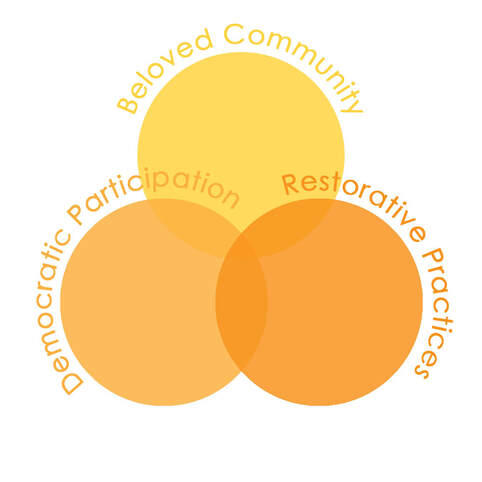

We believe that each classroom is unique, as is each student, each teacher, each school, and each community. One of our core beliefs is that there is not a single “best” way to approach and sequence curriculum; it is the art of teaching to figure out how to adapt and invent approaches to your own context. Therefore, rather than offer a sequenced youth development curriculum, we offer three overarching “curricular guideposts,” each with a set of methods, so that you maintain the agency to choose, adapt, and sequence these methods as you see fit. Many of these methods, though not all, are ritualized: rituals as repeated structures provide consistency that develop a reverence for participation in personal and communal development and reinforce safety, cohesion, and ownership through familiarity. Using consistent, ritualized structures provides the stability necessary for students and teachers to create brave spaces within which students and teachers can become fully human by learning how to prevent and respond to social and individual breakdowns in the classroom. The following diagram provides an overview of Youth Development Curricular Guideposts:

|

The three overarching guideposts are best imagined as a Venn diagram because they share space with one another; for example, one major goal of Restorative Practices is to build Beloved Community, and there is no Democratic Participation without the conflict-solving skills invoked in Restorative Practices. In the methods section, you will notice that some methods are repeated across these guideposts, likewise reflecting this overlap.

Before making choices about how to implement youth development practices in your own classroom, it is helpful to get clear on your purposes. Below are some questions that may help you as you make curricular choices. As you gain experience and confidence, revisit these questions to continually build, revise, and reflect on your approach. You may also check out the Emergent Youth Development Curriculum Sequence that Humanities Amped teachers will be exploring together in the 2019-2020 school year to consider the sequence we are beginning to flesh out in our classrooms. |

- What kinds of youth development supports do students at my school need? What do students in each of my classes need?

- What are my needs? Which methods do I feel confident experimenting with? Which do I require more support or modeling for?

- Based on my students’ needs and my level of confidence, which methods will I experiment with?

- What are my goals for experimenting with these methods? Why?

- With what frequency will I implement youth development practices in my classroom? What frequency of implementation will best support my students? What frequency is realistic for my context?

- How will I assess the results of these methods? How often will I assess and reflect? How often will I assess students and ask them to reflect? Why?

- How will I use the results of these assessments and methods to meet my overall goals? How will I reach out for support if necessary? Who is my beloved learning community, and how can I access them for support?

As we explore, create, and adapt approaches to youth development in our classrooms we have found it helpful to keep in mind that personal development is not easy: not for teachers and not for students. It is a very natural, human response to resist opportunities for growth, and learning is painful when it means we have to let go of old stories and ways of seeing ourselves in the world. Though some might frame this resistance as “bad behavior,” or proof that “it’s not working,” in truth, discomfort, resistance, and conflict are a natural part of the learning process. For critical, justice-oriented classrooms, it is essential to learn how to move through crisis and discomfort. Kevin Kumashiro (2009) explains, “students [and teachers] who are in crisis are on the verge of some shift and require the opportunity to work through their emotions and disorientation” (p. 30). In order to maintain focus on the growth and not the resistance to the growth, it is helpful for teachers to ground themselves as facilitators, whose role it is to make the process easier. As you plan, hit snags, and plan again, we suggest you keep these facilitative meta-questions close at hand:

- How can I make the way easier for myself and my students towards a humanized classroom?

- How do I balance the need for safety and the need for healthy social and emotional risk-taking?

- How do I incorporate reflection, for myself and for my students, throughout these processes?

- How will I recognize when my students or myself need additional care in order to engage in this work in a respectful and responsible way? What kinds of support systems can be tapped into to access that care?

- How will I learn from the breakdowns and challenges I will face rather than shut down when I feel challenged? Conversely, how will I gauge when it is best for me to step back or step out?

- What are my blindspots and biases? If I have identities that are privileged in the dominant culture, how do I learn the humility needed for the unlearning and learning I need to do in order to responsibly engage with my students and their communities?

- How does my identity open and/or close points of contact between people? How do I negotiate the tensions of shared and diverging identities, including the historical weight and social consequences of those identities?

- As a facilitator, how will I access honest feedback that allows me to understand the limits of my own facilitation, make adjustments, and bring in the supports that I cannot provide?

Guideposts and Sequence

Click on each guidepost below to explore.

Click the icon below to see a suggested sequence for implementing the Youth Development guideposts in your classroom.