What is Critical Participatory Action Research?

Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR) is an approach that positions everyday people as researchers of their own social worlds and life contexts. Whereas traditional social science research is carried out by formally trained researchers who may or not be participants of the communities they are researching, CPAR is an approach to research that centers participant expertise, insisting on the ethic of no research about us without us. Stemming from this critical notion that experience is a form of expertise that is too often pushed to the margins, CPAR presumes that critical knowledge is not located among few legitimized “experts,” but rather, among people whose indigenous, or local knowledge, often remain unauthorized by formal gatekeeping institutions. Per McIntyre (2000), there are three principles guiding CPAR:

For Humanities Amped, CPAR is a process for generating student inquiry, systematizing that inquiry through the research process, and making student learning transferable to the “real world” through action projects. We believe these priorities can be the heart of any classroom, and in our humanities content classes we find ways to connect CPAR to historical, cultural, and social knowledge as well as literacy skills (namely reading analytically and writing compositions for a variety of purposes and audiences). Thus, CPAR enables teachers to engage students’ inquiries and build a curriculum that emerges from those inquiries while simultaneously teaching content. In this context, content is not a static set of facts to be memorized nor decontextualized skills to be drilled; instead, content is information that is relevant to students’ lives and provides a set of useful tools for navigating through a problem-solving process. If that sounds familiar, it’s because this is how people gain knowledge and put knowledge to action every day in real-world contexts.

- The collective investigation of a problem

- The reliance on indigenous knowledge to better understand that problem

- The desire to take individual and/or collective action to deal with the stated problem (p. 128)

For Humanities Amped, CPAR is a process for generating student inquiry, systematizing that inquiry through the research process, and making student learning transferable to the “real world” through action projects. We believe these priorities can be the heart of any classroom, and in our humanities content classes we find ways to connect CPAR to historical, cultural, and social knowledge as well as literacy skills (namely reading analytically and writing compositions for a variety of purposes and audiences). Thus, CPAR enables teachers to engage students’ inquiries and build a curriculum that emerges from those inquiries while simultaneously teaching content. In this context, content is not a static set of facts to be memorized nor decontextualized skills to be drilled; instead, content is information that is relevant to students’ lives and provides a set of useful tools for navigating through a problem-solving process. If that sounds familiar, it’s because this is how people gain knowledge and put knowledge to action every day in real-world contexts.

Why Critical Participatory Action Research?

For youth and communities who have been systematically excluded from democratic participation through overt and more subtle forms of silencing, CPAR is a process that helps us see that we have the capacity to ask our own questions, to seek out knowledge in a systematic way, and then to work with others to take action connected to what we learn. Stripping this natural learning process from schools in favor of decontextualized forms of knowledge, which are far easier to standardize, test, and profit from, results in an educational dispossession in which learners lack (1) an understanding of why school matters beyond “achievement” and (2) models of success other than “achievement.” In the meantime, many students (and teachers) experience what Gloria Ladson-Billings (2014) has called “death in the classroom” (p. 77). This refers to the alienation students feel not only in interpersonal relationships in schools, but also, and perhaps even more fundamentally, alienation from the material itself. When students ask, “Why should we care about this?” and the answer given to them is, “To pass (fill in the blank) test,” we are participating in a process of deskilling by isolating the skills and competencies from their inherent, context-filled meaning. It is absurd to expect children to learn in an environment that segregates application and context from knowledge. The result is a form of intellectual death that has dire consequences, pushing many young people out of school and into the circuits of incarceration and low wage labor.

In an ever-destabilized world in which traditional sources of knowledge are no longer able to manage the rapid expansion of information, Arjun Appadurai (2006) argues that the ability to research is a critical tool for survival. He asserts that the “right to research” in such a world is not something that can be reserved for traditional researchers; indeed, the right to research is a central tool of democratic participation. For Appadurai, research in its most basic sense is a means to increase one’s knowledge, a set of tools “through which any citizen can systematically increase that stock of knowledge which they consider most vital to their survival as human beings and to their claims as [global] citizens” (p. 168). Appaduria explains that the right to research is linked to the “capacity to aspire…to plan, hope, desire, and achieve socially valuable goals” (p. 176). Indeed, when we lose confidence in our ability to make sense of the world around us, we also lose our capacity to foster hope in ourselves to act with agency. Throughout its first five years, Humanities Amped has been dedicated to learning how to situate CPAR within high school classrooms. We have come to understand that engaging students in this form of learning is a long-term project that is as much about resuscitating curiosity, confidence, and a sense of hope as it is about the measurable skills that students gain. Indeed, many people confuse the acronym “CPAR” with the similar acronym “CPR” (cardiopulmonary resuscitation), but they aren’t entirely wrong to do so; to some extent, we can approach the capacities awakened through CPAR as if our lives depended on it, because in fact, they do (Rich, 1993, n.p.).

In an ever-destabilized world in which traditional sources of knowledge are no longer able to manage the rapid expansion of information, Arjun Appadurai (2006) argues that the ability to research is a critical tool for survival. He asserts that the “right to research” in such a world is not something that can be reserved for traditional researchers; indeed, the right to research is a central tool of democratic participation. For Appadurai, research in its most basic sense is a means to increase one’s knowledge, a set of tools “through which any citizen can systematically increase that stock of knowledge which they consider most vital to their survival as human beings and to their claims as [global] citizens” (p. 168). Appaduria explains that the right to research is linked to the “capacity to aspire…to plan, hope, desire, and achieve socially valuable goals” (p. 176). Indeed, when we lose confidence in our ability to make sense of the world around us, we also lose our capacity to foster hope in ourselves to act with agency. Throughout its first five years, Humanities Amped has been dedicated to learning how to situate CPAR within high school classrooms. We have come to understand that engaging students in this form of learning is a long-term project that is as much about resuscitating curiosity, confidence, and a sense of hope as it is about the measurable skills that students gain. Indeed, many people confuse the acronym “CPAR” with the similar acronym “CPR” (cardiopulmonary resuscitation), but they aren’t entirely wrong to do so; to some extent, we can approach the capacities awakened through CPAR as if our lives depended on it, because in fact, they do (Rich, 1993, n.p.).

CPAR Project Snapshots: Various Implementations

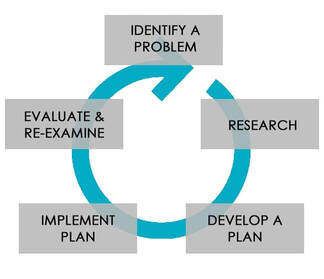

CPAR links action to research through what Paulo Freire defined as the cycle of critical praxis (see diagram): the capacity to interpret and act upon the world in order to transform it (1970).

There are many examples of youth-centered and youth-adult research collectives using CPAR. Humanities Amped teachers learned from some of these models when we were first figuring out how to integrate CPAR into our classrooms. The descriptions below give some examples of how to implement the cycle of critical praxis:

OUtside Examples

Polling for Justice - Public Science Project in NYC

1) The Problem |

Youth are affected by negative consequences in education, healthcare, housing and criminal justice.

|

2) Research |

Poll over 1,000 NYC youth

|

3) Plan of Action |

Theater performance based on research for audiences in NYC. See video here.

|

4) Implementation |

Present and raise dialogue with audiences

|

The Fed Up Honeys

1) The Problem |

The effect of stereotypes on young womyn of color; this includes how stereotypes “oversimplify, reduce, and limit us” (Fed Up Honeys, p. 2).

|

2) Research |

Dialogue, participant observation, archival research

|

3) Plan of Action & Implementation |

Informational website; sticker campaign in which stickers that challenge stereotypes about young womyn of color were put up at sites around the community

|

Humanities Amped Examples

Because we situate CPAR within an in-school context in which we work with students for multiple years at a time, Humanities Amped has begun to think about CPAR across a multi-year trajectory in which students move from a highly scaffolded to a more independent process over time. Below is an example of one student’s experiences moving through three years of CPAR projects: the first description reflects a whole-class sophomore project conducted in small groups of 7-8; the second description reflects a small-group junior project, and the third description reflects a senior’s individual project to demonstrate one student’s recursive progression through three years of CPAR. The narrative between tables demonstrates the students’ progression from her sophomore to senior years.

School Pride, Student Rights, Social Support

Humanities Amped 10th Graders "Triple s" 2016-2017

1) The Problem |

The problem is that students feel as if they don’t have any say so in their learning environment. Most students argue that there’s a need of school pride by students, acknowledgement of student voice, and improved climate.

|

2) Research |

We surveyed 631 students at McKinley High to document student voice regarding problems and successes at McKinley. We also conducted 9 dialogues in other classes at McKinley in addition to making observations through field notes to document student voice regarding improving McKinley.

|

3) Plan of Action |

We will use the data from these surveys, dialogues, and filed notes to conduct sidewalk science, group circles, and online surveys to find out more about student voice to use in teacher workshops. Students will create a document as text to facilitate dialogues with the faculty and staff in order to contribute student voice to school climate.

|

4) Implementation |

This action plan will likely be implemented in May and hopefully will continue through next year; in other words, there will be an ongoing cycle of implementation and new research leading to a new action plan until student voice is fully incorporated into the power structures at McKinley.

|

Six of the eight members of “Triple S” continued to research educational issues for their junior CPAR projects. The next description demonstrates how three of these group members joined with two students from a different sophomore group in their junior year to research how youth can be empowered in schools by learning about and transforming adultism in schools. These students combined the knowledge gained from their sophomore year from their sophomore projects with new knowledge about adultism and subsequently refined their learning and honed their research.

Empowering Youth by Overcoming Adultism

Humanities Amped 11th Graders 2017-2018

1) The Problem |

Adults abuse their power in various community settings without realizing it.

|

2) Research |

We conducted surveys, dialogues, and story circles to understand the relationship between age and authority and how adults abuse power.

|

3) Plan of Action & Implementation |

We presented our research to various audiences at McKinley to get more feedback on how we see adultism at McKinley. We also used music to bring people together and learn how creativity can overcome power.

|

The following example of a senior project demonstrates how one student from the junior group refined her research from her sophomore and junior years even further by applying a critical race lens to student voice and adultism in schools. Her senior research focused on the lack of Black male teachers in schools and revealed a cycle contributing to the lack of Black male teachers that is rooted in the ways Black males are treated in schools, which connects to her research on student empowerment and adultism. Thus, these three project examples demonstrate recursivity and emergent curriculum in CPAR curricula construction. More specifically, this senior was able to identify the root of the problem in her senior research because she had studied student voice, adultism, and racism from various angles and through various methods over her sophomore, junior, and senior years. Additionally, as teachers, we had to tailor readings for this senior’s project; however, as she presented to the class for feedback, her peers not only engaged with her content, but also recalled and applied the knowledge gained from previous years of CPAR which not only helped them to understand Ashanta’s research, but also provide emergent threads of thought and connection for Ashanta.

Black Male Teachers: The Mass Extinction

Humanities Amped Senior Ashanta Gleason 2018-2019

1) The Problem |

There is a lack of Black male teachers in schools.

|

2) Research |

I found statistics regarding Black male teachers in addition to conducting questionnaires, surveys, and a graffiti wall to ask young people about their experiences with Black male teachers.

|

3) Plan of Action |

I will celebrate McKinley’s Black male teachers and Black student teachers to honor them as positive Black eductor representatives as an incentive for them to continue teaching and encourage other Black males to teach. This event will also be an opportunity for students to learn about the profession.

|

4) Implementation |

I held the “Bringing B-B-Q to Education” event at McKinley during which a Black school board member gave the keynote address, I shared my presentation, awarded Black administrators with certificates and teachers with trophies, and honored the Black male teacher who has made the biggest difference in my life.

|

Foundational Ideas, Values, and Goals of CPAR

In the summer of 2015, Susan Weinstein and Anna West from Humanities Amped attended the Public Science Project’s Summer Institute. During the institute, Michelle Fine, a scholar at the fore of building collective scholarship and a public pedagogy through CPAR, outlined the central values that frame the approach:

- CPAR is not a method; it’s a politic, a challenge to status-quo assumptions about where knowledge lies. Therefore, CPAR

- Is framed as a collective public enterprise recognizing that knowledge is widely distributed but narrowly legitimated;

- Critically reframes problems to dig deeply into the histories, structures, and circuits of privilege and dispossession;

- Troubles status-quo categories and constructs that are often over-simplified, ignore intersectionality, perpetuate damaging frames of the people and their power, and disregard these people’s desires and possibilities; and

- Maintains an ethic of “No research about us without us”

- Is framed as a collective public enterprise recognizing that knowledge is widely distributed but narrowly legitimated;

The Recursive Classroom Structure of CPAR

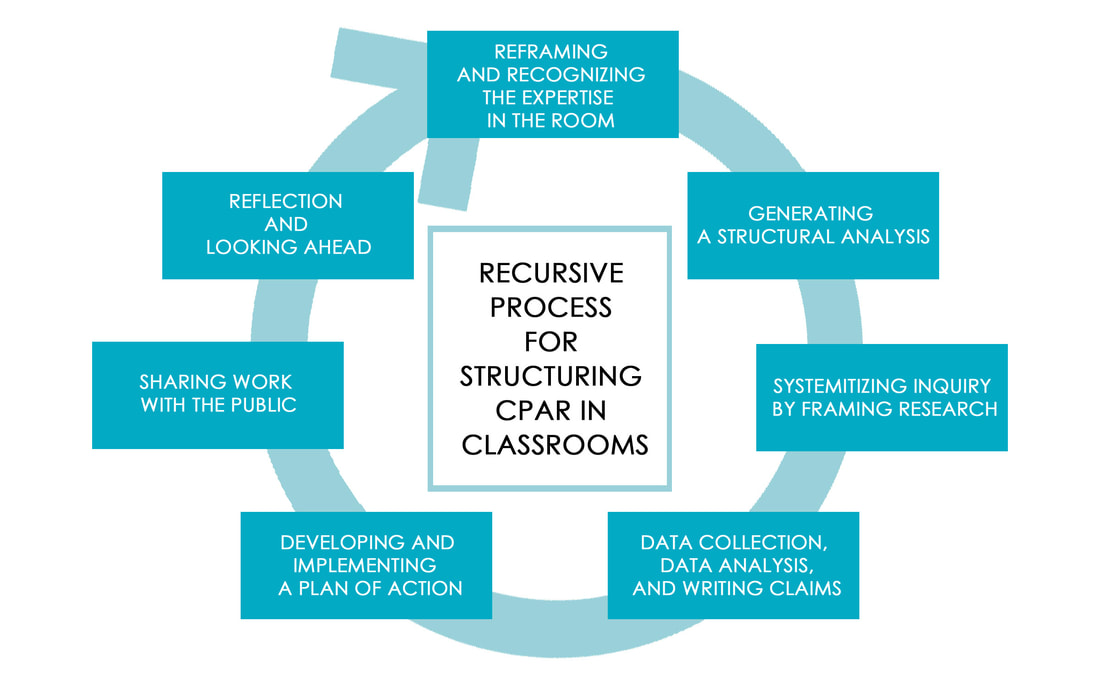

In Humanities Amped classrooms, we have come to understand CPAR as a pedagogy that typically moves through seven phases, though these phases are not necessarily always exactly in the order shown in the graphic above. These phases are recursive, meaning we may move back and forth across the phases as needed at different points. For example, when analyzing data that students have collected, we may go back to generating a structural analysis and do some more reading and theorizing; or we may begin by developing an action plan to open a project, use the action as a way to collect data, and then step back to generate a deeper analysis and recognize the participant expertise of students to develop the project further.

We also have come to understand that for students to internalize this process, they must experience it multiple times. As the charts in the “Snapshots” section illustrate, students may have multi-year experiences with CPAR. Consequently, teachers can make different choices over time, giving students more autonomy over these phases as they gain a deeper understanding of the process themselves. For teachers who are not able to create a multi-year context for practicing this process, we suggest creating ways for students to practice the process in “quick and dirty” ways that take students through the whole process in a short time period before diving more deeply into a longer and more detail-oriented version. When students have internalized the steps, they feel more confident and are less likely to feel out of their depth with this kind of open-ended, recursive learning.

Figuring out where to begin is a tricky back and forth between planting generative thematic seeds, listening and responding to our students’ interests, and strategically tapping into community collaborators. Choosing themes is a tricky part of the process which can also influence your approach. Teachers do have a powerful influence over the kinds of themes that students will choose through the kinds of readings we assign, the people we bring in to speak to students, and the way we sequence the process; no matter how it is done, we strongly believe that identifying generative themes for CPAR is a process that must happen with students, which is always a dialogic back and forth process of listening to one another to understand what themes are most resonant.

We have come to understand that educators who engage CPAR must have an underlying commitment to emergent curriculum (Biermeier, 2015). Emergent curriculum, which, in the case of CPAR, makes room for students to define inquiries and make choices, can provoke both personal and institutional anxieties for students, teachers, and those shaping school policy. These tensions must be navigated if we are to develop classrooms that truly respond to students’ needs and interests. We hope these phases reduce some of that anxiety, making it easier to engage a flexible process that centers students’ interests and needs.

Figuring out where to begin is a tricky back and forth between planting generative thematic seeds, listening and responding to our students’ interests, and strategically tapping into community collaborators. Choosing themes is a tricky part of the process which can also influence your approach. Teachers do have a powerful influence over the kinds of themes that students will choose through the kinds of readings we assign, the people we bring in to speak to students, and the way we sequence the process; no matter how it is done, we strongly believe that identifying generative themes for CPAR is a process that must happen with students, which is always a dialogic back and forth process of listening to one another to understand what themes are most resonant.

We have come to understand that educators who engage CPAR must have an underlying commitment to emergent curriculum (Biermeier, 2015). Emergent curriculum, which, in the case of CPAR, makes room for students to define inquiries and make choices, can provoke both personal and institutional anxieties for students, teachers, and those shaping school policy. These tensions must be navigated if we are to develop classrooms that truly respond to students’ needs and interests. We hope these phases reduce some of that anxiety, making it easier to engage a flexible process that centers students’ interests and needs.